Child Learning | Curriculum Overview

What do we teach, and when do we teach it?

Curriculum rationale and definition

Ford and LAT's Curriculum can be broken down into four distinct, but interconnected parts:

-

Intended Curriculum: the required knowledge, skills and understanding that might be written down in the specification for a unit of study.

-

Enacted Curriculum: the curriculum that the pupils actually experience as delivered by their Teachers, each Teacher applying their own filter, adding or subtracting content, developing a unique combination of tasks and resources.

-

Assessed Curriculum: the knowledge, skills and understanding that students encounter in their assessment – normally a subset of a much wider curriculum.

-

Learned Curriculum: the knowledge, skills and understanding that students are left with at a later time.

This definition can also be represented in a visual way that maps LAT’s vision to achieve a broad Curriculum for all its pupils, parents and staff. The image below details how Teachers plan by first identifying the key objectives, concepts, skills, knowledge and vocabulary that will be taught. Teachers then move into a progressive process of designing and sourcing the relevant and most effective Teaching resources, models and images. Next, Teachers identify how best to capture assessment on pupil outcomes and then finally highlight further behaviours and experiences that the wider curriculum is intended to bring.

Philosophical approach explained

The Learning Academies Trust curriculum plan is built on a robust and considered philosophy related specifically to influences such as, Cognitive Science, Neuro Science, national academic standards and community needs. The design is built on secure and proven foundations referenced by Leaders in the Scientific fields linked to the development of long term learning and memory. LAT members believe that the learned curriculum is the curriculum that actually counts for pupils as they strive to build informed links between theories, proven study, facts from history and their own ideas.

LAT members believe that disadvantaged students often need to rely much more on the diet of deliberate learning that they receive from being in school. A good curriculum empowers children with the knowledge they are entitled to and is primarily based initially on the National Curriculum. Phrases such as, ‘If children don’t remember what we have taught them, then even the richest curriculum is pointless’ seem ever more relevant as educators strive to assess their pupil’s depth of understanding. Key reference points for this belief stem from experts such as, Memory is the residue of thought Professor Dan Willingham (Psychologist and author), Learning is a change in long term memory. If nothing has been changes in long term memory then nothing has been learned” Professor Paul Kirschner (Educational Psychologist & Author), ‘You can always Google it’ is the most dangerous myth in education today. Dylan Wiliam (Educationalist) and Learning is defined as an alteration in long term memory Sweller, Ayres & Kalyuga (2011). Other key references are of interest when measuring the purpose, worth and effectiveness of LAT’s Curriculum, most notably, Martin Robinson’s, Trivium, where he debates the need for pupils to be taught that the arts of knowing, questioning and communicating unlock the Curriculum’s true potential. Ofsted have also influenced Curriculum design by offering a structure for staff to frame their thinking. The collective parts of Curriculum thinking can be organised as three interlinked and key elements 1) intent 2) implementation 3) impact.

LAT’s curriculum offers pupils a core set of objectives and goals that all are entitled to receive access to. Staff continuously design and refine their approaches to measuring the impact of this curriculum deliberately focusing on how each of the LAT School personalise and contextualise learning experiences. Staff work in teams to meticulously select what is taught, organise this in a progressive and deliberately challenging order and then integrate and apply within their own Schools. Pupils and their families benefit from having peers from across the LAT’s influence to link with and collectively learn with/from. The value of learning for learning’s sake is shared and thus empowered beyond individual settings. Staff work in cross School disciplinary teams to design schemes of teaching, learning and assessment, that are deliberately progressive and challenging in nature. Staff benefit from having colleagues as experts to quality assure and review stages of planning. They organise themselves into dynamic subject based hubs all of which focus in on creating excellence within Schools. Subject Hubs challenge and support each other’s professional development aiming at all times to network their thoughts and professional relationships beyond those found within the LAT itself.

Curriculum design is grounded by key subject drivers. These are History, Geography as well as core Science, Maths and English. History and Geography act as fundamental perspective drivers that add empathy and perspective to learning. They act as a directional compass to centre and root learning, whilst prompting the direction of pupil’s further thoughts and ideas. Studying key concepts about the past (History), ‘Then and Now’ and linking to other places (Geography), ‘Here and There’ enables pupils to create their own opinions (based on factual knowledge and/or accounts evidenced from key sources of credible information) of how these concepts might develop in the future. Relating learning back to a pupil’s own version of the here and now, creating curiosity, expects pupils to both study and think deeply about how these driving concepts interrelate with each other and become relevant to a pupil’s everyday life.

Pupils continuously look not only to remember facts, but to apply knowledge beyond discrete subjects areas to create a rounded and broad knowledge base and extended schema of understanding. Staff continuously review how to implement a Curriculum that enables pupils to study less content, but in more depth than ever before.

A culture of continuous improvement, that remains invitational at all times, is a by-product of this cultural exchange of ideas and research. Workload is reduced by sharing resources and expertise across all LAT Schools, whilst at the same time linking staff to develop rigorous and cross LAT assessment judgements. There is a continuity in LAT’s curriculum design offering pupils and their families an entitlement for all model of delivery. All stages of planning are co-constructed and co-quality assured by Subject Hubs. Pre-defined subject drivers, linked specifically to key concepts, are taught, learned and assessment. This is consistent across all LAT Schools, offering LAT members a sense of cross School rigour, excitement, focus and attention to excellence. Staff support each other to review pupil outcomes searching for subtle differences to the a) depth of pupil’s understanding b) impact of TL&A strategies on pupil’s engagement c) impact on the quality of final outcomes and relevant products. The LAT’s, ‘Believe we can…Together we will’, ethos empowers staff to create the finest curriculum experiences that aim to create learning that is, memorable, relevant, authentic in purpose and imbedded in knowledge, skills and concepts. Research and inquiry informed practice sit at the heart of staff professional development. This sense of professional curiosity and exploration, drives a process that is committed to continuous reflection and refinement of practice. Philosophies linked to LAT curriculum design are therefore, in their very make up and nature, continuously evolving.

'Together we can...'

Curriculum Organisation | Building empathy and perspective by connecting curriculum driver subjects

Building empathy, grounding, and a sense of perspective through LAT Curriculum Design.

LAT’s curriculum design is grounded by key subject drivers. These are History, Geography as well as core Science, Maths and English. History and Geography act as fundamental perspective drivers that add empathy and navigation for study. They act as a directional compass to centre and root learning, whilst prompting the direction of pupil’s further thoughts and ideas. Studying key concepts about the past (History), ‘Then and Now’ and linking to other spaces and places (Geography), ‘Here and There’ enables pupils to create their own opinions (based on factual knowledge and/or accounts evidenced from key sources of credible information) of how these concepts might develop in the future. Relating learning back to a pupil’s own version of the here and now and creating curiosity, LAT’s curriculum expects pupils to both study and think deeply about how these driving concepts interrelate with each other and become relevant to a pupil’s everyday life.

Staff lead pupils through a concept continuum. Key Historical and Geographical concepts are introduced, explored, imbedded. Staff plot this journey and ensure that concepts become more sophisticated as they age. Pupils, therefore, move through progressive stages of sophisticated concept thinking.

Staff planning, models this journey, and points at key milestones of knowledge, for pupils to grasp hold of, organise and integrate into their world and existing understanding. Thinking moves between comparing and contrasting the relationship between the past (how it shapes events today), and the evolution of differing places / cultures. Learning from what has gone before inspires staff and pupils to think carefully about solving real world problems. Pupil’s study creates a rooted connection and sense of moral responsibility for their / our planet, for the here and now as well as the future.

Assessment of the depth and degree concepts are imbedded within pupils understating is taken as a continuous loop. Subject based knowledge Organisers, alongside lesson plans, are designed by Schools, and used as a script by which to assess whether a pupil can:

Assessment of the depth and degree concepts are imbedded within pupils understating is taken as a continuous loop. Subject based knowledge Organisers, alongside lesson plans, are designed by Schools, and used as a script by which to assess whether a pupil can:

- Recall knowledge with confidence about chronology, theory, factual details, and linked vocabulary.

- Explore and question knowledge forming their own rounded opinion, schema, and insight, linking theory and opinion to differing contexts.

- Share and communicate knowledge to others, shaping it into a personalised version, which is relevant to a pupil’s own context, (and/or that of others) whilst making authentic links to real life. Making audiences think differently should be a key marker of assessment and an insight into a pupil’s depth of clarity, but also their degree of curiosity and interest.

LAT staff have come together to collectively select subject content and organise their curriculum. They have co-constructed both its values and its purpose. They have integrated this into the plans of each School forming the basis of an ‘entitlement for all’ curriculum model. In addition to core termly subject drivers, History, Geography, Science, Maths and English, staff have added layers of study depth via the remaining National Curriculum subjects. As well as being of inherent worth as stand-alone subjects, these remaining subjects partner and compliment the core. They are ultimately pivotal to the core making sense. Where appropriate, and not in a superficial sense, subjects partner to create topics of learning. This gives core subject drivers additional and deeper meaning through real life application. For example, applying Writing and Grammar structures to real life (cross subject) topics gives Writing and Grammar a purpose and use beyond just the otherwise isolated subject matter itself. Through an intense and deep dive style application of knowledge, skills and concepts, pupils create their own ideas, produce their own authentic products and begin to explore how to solve real world problems.

Each term, Staff deliver topics that take deep dives into specific subjects with the intention of pupils developing informed and robust knowledge schema. Subjects are carefully positioned throughout the academic year and are partnered with others that offer enhanced opportunities for knowledge to make deeper sense. This process forms the bases of a specific subject based cross LAT moderation and quality assurance process. Staff use the curriculum’s organisation to inform them of what they should quality assure, but also when. For example, during the Autumn Term, all staff from across the LAT will work together to carefully monitor, capture, compare and contrast key evidence from their Design and Technology teaching, learning and assessment. Staff work in teams to evaluate outcomes across termly subject drivers, and over time, create vast portfolios of age / stage and subject specific expectations. These are collectively quality assured ensuring that robust forms of assessment and data are continuously developed and communicated with all staff, pupils and parents. This data informs staff about which teaching, learning and assessment methods are having the greatest impact on pupil’s learning. Staff are then in a position to make informed decisions of how to refine their practice within specific subject drivers. For example, by the end of Autumn Term, all staff would have evaluated cross LAT outcomes in subjects, but would have also taken a deep dive into Design and Technology. Clarity on what LAT ‘excellence’ looks like in this subject is then transmitted across all stakeholders.

During the Autumn term, staff take a deep dive into the knowledge and skills that underpin concepts related to Design and Technology. Other subjects link where appropriate. Spring Term has a focus on developing Art knowledge and skills and using these as a vehicle for expression and communicating concepts across subjects. Staff tune into these focus areas and understand that over time, they will build sophisticated banks of refined resources. The intention is to reduce staff workload, cover less content, but in more depth, whilst giving confidence to all that these resources are continually refined and evaluated for effectiveness.

Teams working together, with a common focus, articulating what works, why and how is a crucial benefit and outcome of LAT’s Curriculum organisation. A true celebration of learning is also made possible through cross School subject links. Staff, pupils and their families not only know what is being taught across all LAT Schools, but also when it is taught. They are, therefore, able to seamlessly link with each other sharing and comparing examples of learning related to the exact same subject matter.

This method of curriculum organisation enables LAT School members to become a unique community of networked learners.

Creating an authentic sense of cross School collective responsibility is deliberate, but a secondary outcome of LAT’s curriculum organisation, is that of cross School excitement and interest. Understanding how one pupil’s learning is part of a wider connection with other LAT learners brings a sense of connectivity and belonging. Each LAT School is encouraged and has freedom to add further worth to the curriculum model, by delivering schemes that provide contextually relevant meaning and structure. Schools create their personalised subject areas and guiding schemes of work, for example, those related to bespoke values, behaviours and mission statements. This enables each LAT School to root themselves in their communities. Remaining real, authentic and relevant to the communities that they serve, becomes a key additional subject driver for all LAT Schools.

Intent | Planning Matrix

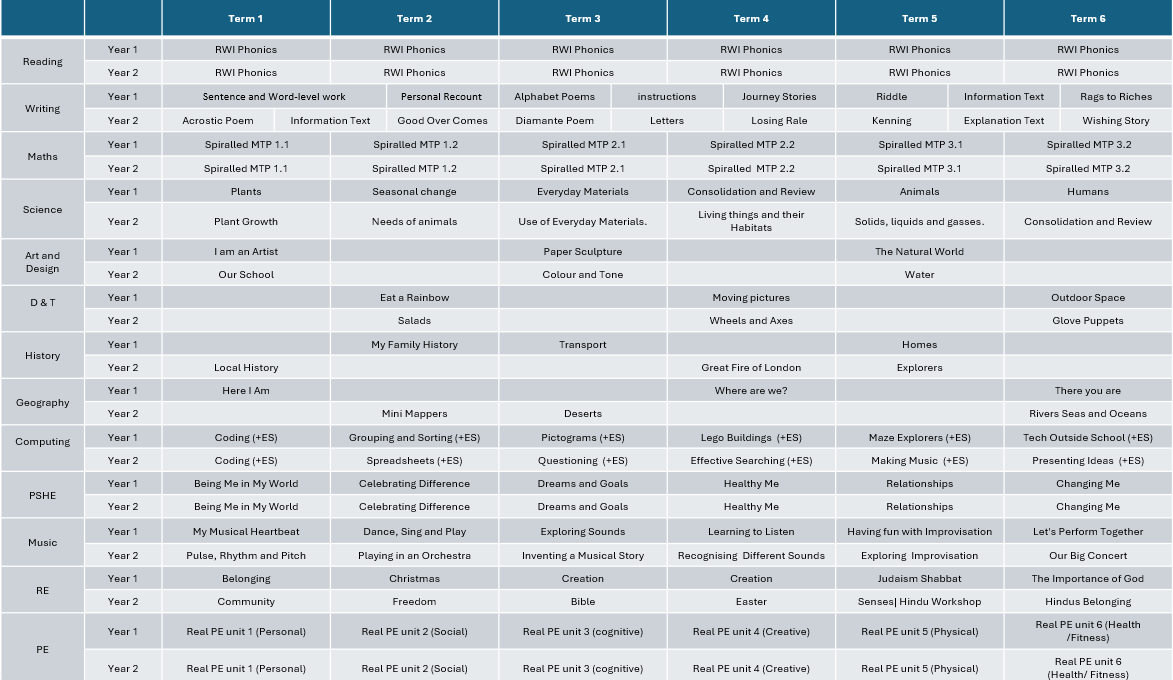

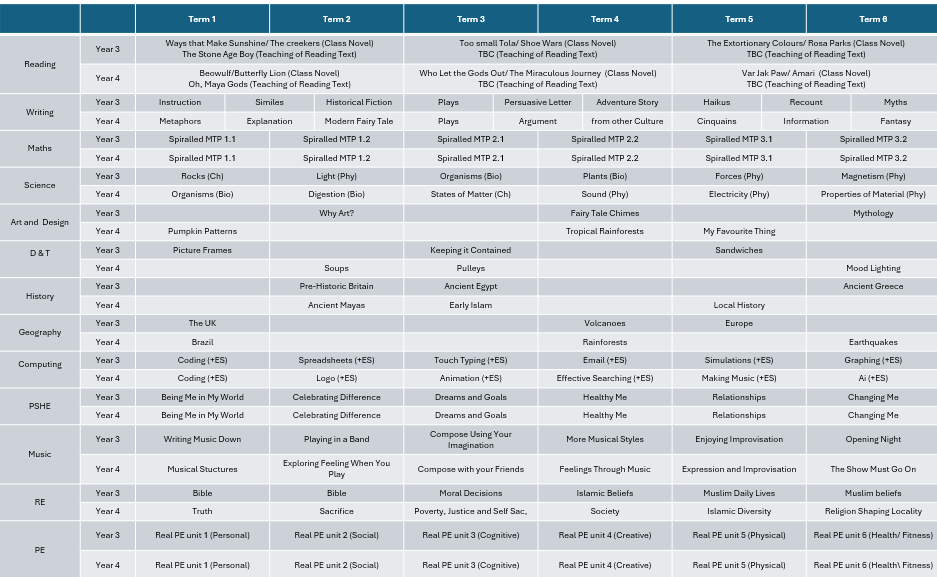

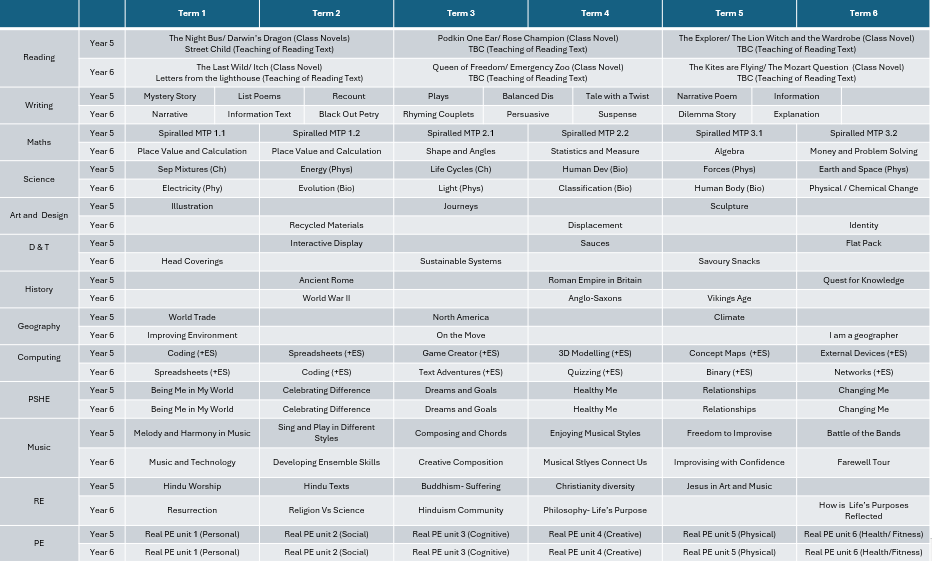

Staff from all LAT Schools have mapped their subject content and coverage across each term. The matrix plan is designed to guide both mixed age as well as single aged year classes.

Curriculum Overview Years 1 and 2

Curriculum Overview Years 3 and 4

Curriculum Overview Years 5 and 6

Notes of reference to inform curriculum rational and practice

Curriculum and Cognitive Science

Referenced: https://rosalindwalker.wordpress.com/2019/08/06/curriculum-and-cognitive-science/

What do we mean by curriculum? And why is curriculum so important? How should curriculum planning and execution be informed by cognitive science? These are, in my opinion, questions of the utmost importance.

What do we mean by curriculum?

Curriculum is the substance of what is taught. It is the things we want students to learn while they are with us, and it is structured over time, since learning happens in time. We will return to this later.

Why is curriculum so important?

In recent times, it was widely believed in teaching that knowledge was a low-level thing and that it wasn’t really worth learning knowledge because we should be doing high-level stuff like analysing, synthesising and evaluating instead. We now know that to be false. Research has shown conclusively that skills like evaluating are domain specific. Knowledge is what we think with, and we can only be curious about things we already know something about.

We now know from cognitive science that the mind can be conceived of as comprising two “parts“: the working memory and the long-term memory. Working memory is what we think with, and space there is very limited: it can hold only around five items at a time. If you try to hold more, something will drop out.

The long-term memory is where the things we have learned are stored. When we encounter a problem like a puzzle or an essay question, we can bring information up into our working memory from our long-term memory. The exciting thing here is that there are no known limits to space in the long-term memory. It’s not like a jar that can get full up. In fact, the more you know, the easier it is to learn new things. And the more you have stored, linked and automatised in your long-term memory, the more space you can free up in your working memory for dealing with challenging material.

So curriculum is absolutely critical. The substance of what we plan for our children to learn will form the resources they have to draw upon when approaching problems. Knowledge in students’ long-term memory will be their toolbox when reading texts, writing essays, wrestling with problems, and thinking in general. Curriculum stocks the toolbox.

If we want students to get cleverer, to be better able to analyse, evaluate, and synthesise, to be effective critical thinkers and problem solvers, there are no short cuts. We must teach them lots of knowledge, and help them to remember it.

This knowledge forms our curriculum. When we build a curriculum, we have to make choices: choices about what to include, how we exemplify and illustrate, how we practise, and in what order everything comes. These decisions are not trivial. In planning curriculum we are planning to build the knowledge that our students will use in order to think – potentially for the rest of their lives.

How should curriculum be informed by cognitive science?

To plan our curriculum, we must begin at the end. We must ask: What is it that we want our students to leave us with, that they did not have when they arrived?

What we want students to gain from their time with us is rich, powerful and well-organised knowledge that they can use to think with and to understand the world and themselves. Cognitive science gives us the model of knowledge as a schema: a web of interconnected pieces of knowledge. When students join us, they have a limited schema in our subject: few pieces of knowledge, few connections, and possibly misconceptions:

We want them to leave us with a dense, well-linked and well-organised schema – in other words, we want them to have learnt lots of high-quality knowledge in the subject.

As experts in our subject, we have a good schema in our heads for our subject.* However, brains being what they are, we can’t just take a copy of our schema and insert it into the brains of our students. Schemas aren’t copied: they are built.

Time and content are the two critical characteristics of curriculum.

When we make houses, we don’t see a house, copy it, and paste it onto the ground. We look carefully at the parts of the house and their materials, we look at how they will all fit together in the end, the roles of the walls, struts and beams, and we plan out a sequence of building so that we can build the house over time. We want it to be beautiful, long-lasting, and for each subsequent piece to be supported by what has already been built. We must do the same with curriculum. The schema is like a house and we must plan how we build it.

In cognitive science, building a schema is known as encoding. Effective curriculum planning and implementation are informed by cognitive science so that encoding can be successful.

In planning curriculum we must consider first the content itself, or rather the content headlines. This will be a mixture of substantive and disciplinary knowledge: the claims or pieces produced by the discipline, and the rules and procedures for working within the subject. These are the main features of the house: the walls, roof, doors and windows. In science, there are fewer decisions to be made regarding content headlines, and this is for several reasons: it is a “vertical” subject with relatively well-agreed necessary prior knowledge for further study; and the national curriculum and specifications in the UK are pretty good, with a good level of ambition and preparation for further study, and few glaring omissions; they are quite detailed. We might decide to add in additional content, perhaps because it supports other knowledge and makes it more meaningful and memorable. We might show our students the formula for resistors in parallel, for example, because it is much more satisfying and less frustrating for them than just being told “the total resistance will be less – never mind how much less!”

Were we not furnished with a reasonably well-designed national curriculum/specification, we would have to ask ourselves, what is the knowledge with the highest leverage? What knowledge brings the most understanding? What knowledge opens up the world the most? What will allow students to succeed at A-level if they pursue it? What will enrich their lives even if they choose other A-levels? And indeed, we can surmise that these are the questions that were asked when this national curriculum was created, since it is largely good.

In other subjects and other contexts, there are many more decisions to be made around content. In more “horizontal” subjects like history and literature, there is no obvious and finite set of foundations – you have to leave out some things, in fact you have to leave out most! The political and ethical implications here are significant but not insurmountable, as Christine Counsell shows here.

These decisions about the headlines of what to include in curriculum are critical because of cognitive architecture. If we want students to have a powerful schema, it must contain the components that apply in the largest numbers of contexts, that best illustrate the important concepts, and that give explanation to the most and most significant phenomena. You can’t think about something you know nothing about.

It is important to say here that these main features, these headlines, are not equal to the curriculum, just as the main features of the house are not equal to the house itself. They are key but they are not the totality. So even if your exam specification is perfect, it does not equal the curriculum.

So we have decided the content headlines of our curriculum. Next we must think explicitly about the links between these things. In addition to being more detailed, a key difference in the schema of experts compared to novices is that an expert’s schema is well-organised. So I know that electrolysis, batteries, and bonding are all related by their explanation in electron charges, but this is not clear to the novice or student. We need to map out these links in order to inform both our sequencing and our explanations: these will in turn help our students to build their own well-organised schema. When we are planning to build our house, we need to know which parts will be joined, which parts will bear load and which parts will push or pull on other parts. This will help us to plan the order of building, the materials and the techniques.

The builder must carefully map out the sequence of parts to be completed in order for the house to be successfully built. You probably start with foundations, and then walls, then floors and roof, then plastering. If you get this sequence wrong then the house will fall down. It is the same with curriculum. We must take students on a journey where later content makes sense because of earlier content. Where an area is reliant on a threshold concept, we need to have taught and secured that concept first. We are helping students to build a strong and successful schema. You can’t build a roof in mid-air.

Now we need to plan out the fullness of the curriculum. How will we explain each concept? What language do we need to define? What diagrams, stories, and examples will be the best choices to help our students to understand and build their schema successfully? What is the hinterland that feeds the core? The builder plans the details of the materials, tools, and construction. If you want an effective way to guarantee and preserve this careful planning, I have found booklets to be indispensable.

Because the strength and utility of an expert schema comes in part from the number of links between items, we must plan our curriculum to build as many links as possible. A common misconception around cognitive science and curriculum is that interleaving is a practice of splitting up topics and mixing them up: this is not what is meant by interleaving and is not an advisable practice!

What we should be doing however, is planning in our curriculum detail, where we will make links back to previously studied content, and where we will foreshadow content still to come.

An effective schema is not only strong, it is accessible too. Throughout our curriculum we must schedule spaced retrieval practice in order to build retrieval strength, so that our students can draw upon their learning in the future. Though I would not strictly include retrieval practice as a curricular item, I mention it because a good curriculum without retrieval is a wasted one. It’s no good building a beautiful house if you can’t get to it because the road is closed.

A well-planned curriculum is beautiful. It is rewarding both to create and to teach, and it should lie at the heart of everything we do. Our subjects deserve to be passed on to all students, and our students deserve to learn this wonderful knowledge. Through curriculum, we build and treasure.

*Though we probably have some gaps and must be confident about addressing these if we want the best for our students.

** Spaced practice, on the other hand, where the revision of already encoded material is split up and spaced, is an effective method for building retrieval strength.

Assessment Rationale

Ford has built an assessment framework that informs the schools about the impact of two main aspects of the Teaching and Learning process:

1: The depth of a pupil's knowledge, understanding and ability to make links in learning

2: The ability for pupils to apply procedural knowledge to skill-based activities

Assessment will be used for the following purposes

To ensure that pupils are provided with accurate feedback to support their learning and know their next target.

To ensure that teachers are aware of the next steps in learning to support quality first teaching.

To monitor standards, set high expectations and monitor progress over time.

To provide parents with a clear understanding of their child’s achievements and progress.

To provide a reflective process which supports pupils to monitor and evaluate their learning

To provide MAT wide comparisons for directors and other stakeholders.

Assessment is taken both formally, with snapshot tests using summative assessment tools, such as NFER and SATs, but also informally using ongoing dynamic school based formative procedures.

Influences

To support Teachers ability to make judgements on their pupils depth of understanding, and the effectiveness of their teaching, LAT has been heavily influenced by the work of Martin Robinson and his theory of Trivium. The influence of this theory varies according to the national curriculum subject being assessed. Using Trivium as a guide, staff work within a framework to formatively assess whether a pupil can:

- Recall knowledge with confidence about chronology, theory, factual details and linked vocabulary.

- Question and Explore knowledge forming their own rounded opinion, schema and insight, linking theory and opinion to differing contexts.

- Declare, Share and Communicate knowledge to others, shaping it into a personalised version, which is relevant to a pupil’s own context, (and/or that of others) whilst making authentic links to real life. Making audiences think differently should be a key marker of assessment and an insight into a pupil’s depth of clarity, but also their degree of curiosity and interest.